Introduction

I don’t know how many parts this will take. Batteries are a staple of life if you have anything portable that emits light or generates sound that you don’t crank with your arms.

Fortunately my understanding of them has increased quite a bit in the past 12 years of consumer electronics design and now you get to benefit from what companies paid for me to learn.

Here is an old Polaroid of me working on my first robot, 1979. Circled are flooded NiCad cells I bought mail order from a surplus house; I gave my mom cash and she wrote a check. Acid electrolyte, vents, real dangerous stuff. I’m sure I drank from the garden hose later that afternoon after riding my skateboard with urethane wheels.

Some vocabulary:

A cell is the fundamental unit of charge production and its chemistry determines the voltage

A battery is a collection of cells, like a magazine is a collection of pages

Voltage is pressure, the “want” to get something electrical done; units are volts and abbreviated V

Amperes are the flowing of current that get that that something done; units are abbreviated A

Capacity is flow times time, like volume, and the abbreviation is Ah (ampere-hours or when that is too big, mAh which is milliampere-hours)

C is the measurement of the capacity of the battery and it is used in discharge and recharge rates. It is an ideal and depends on the discharge rate so the “water tank” analogy breaks down here; heavy discharges yield a lower actual capacity. This is because the chemistry takes time to regenerate. Most C values assume you will discharge the battery over 20 hours which in the context of this blog and our applications is fairly useless. More on this later.

Quiz

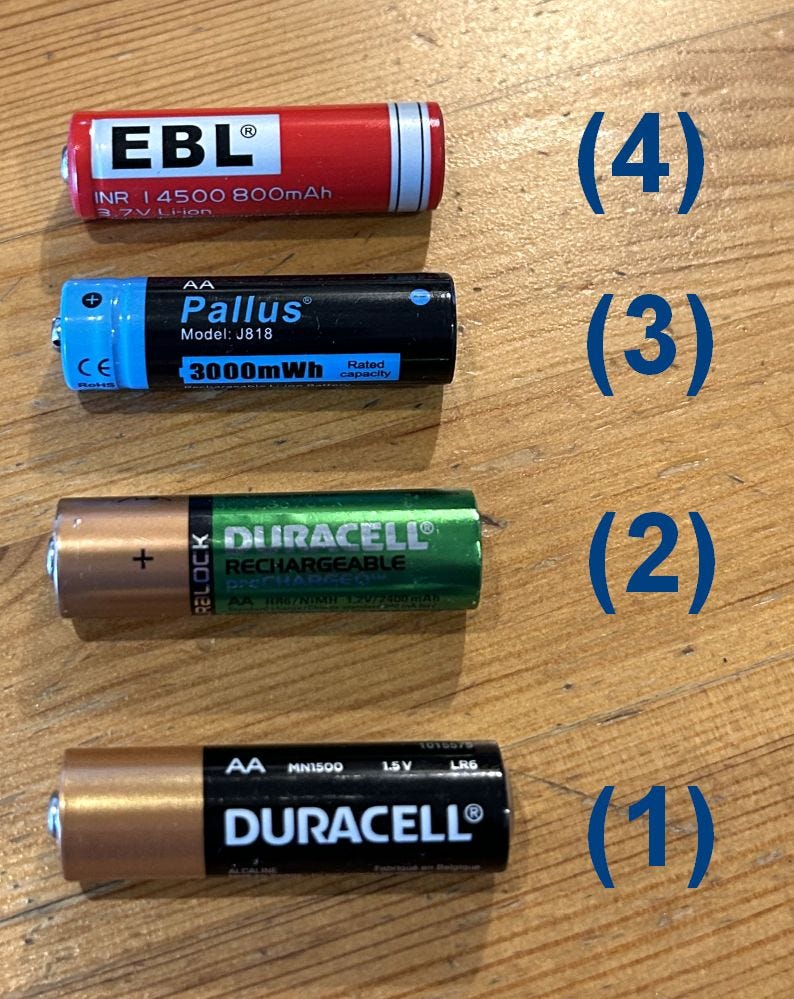

Q: In the above image, what do cells 1-4 have in common?

A: They are the same size as the usual AA cell you are familiar with. That is all.

Cell (1) is a standard Duracell MN1500 alkaline, non-rechargeable, around 2850 mAh capacity. The battery chemistry pops out 1.5V. We all grew up with this or multiples in 6V lantern batteries or 9V transistor radio batteries (both true batteries, not cells). This is called a primary cell since the chemistry is one-way and not rechargeable.

Cell (2) is a Duracell rechargeable NiMH (nickel metal hydride), 2400 mAh that pops out 1.2V - often an issue in devices expecting 1.5V cells so you see the low battery warning. This is a pretty impressive design because typically rechargeable cells have 1/2 the capacity of a primary cell but this dude is tracking up there with (1).

Cell (3) is a rechargeable Pallus lithium ion of capacity 3000 mAh with a special embedded circuit that presents 1.5V on the terminals to fix the shortcoming of cell (2). It requires a special recharger. I could not find a website but they are available online at eBay and that river store and I think the idea is pretty sweet.

Cell (4) is an EBL lithium ion rechargeable, same chemistry as (3), which presents a native 3.7V at the terminals. It is pretty specialized but some Chinese flashlights that expect a 1.5V alkaline cell run brighter and fine on this. You will need a general charger for lithium ion cells; I love the one from OLight but that is discontinued. I have had good luck with this TrustFire unit.

Next Up

Why do I have these four different cells on the shelf? We’ll discuss their intended uses in the next part and how they can benefit you.